Poster Artist Feature: Dennis Larkins Interview

DL: I reached out to Peter McQuaid to see if he knew of a collector who would be interested in some of my original rock poster art. He said, “I might know just the person”, he called back and gave me Roger’s number and said I should give him a call. I did and it took about 2 seconds to conclude that deal. Then Roger told me about Moonalice and the poster series they were doing. He asked if I would I be interested in being part of that. I told him absolutely and over the years have done quite a few posters for Moonalice, Doobie Decibel System and other projects of Rogers.

I recently had a call with Roger, and we reminisced that who could have predicted that this Moonalice series would be over 1400 posters, not to mention the DDS and other posters along the way. And it’s still on going. Who knows where it will end? It has been an honor and a privilege to be a part of something so big. I think even now and certainly by the time it is done. It will be the largest single body of rock art ever created for a single band. It will definitely be a world record and it has included some of the great artists of all time… Stanley Mouse, Wes Wilson and a host of others. Just being a part of that company of artists is a wonderful thing. It just it reminds me of that John Lennon quote, “Life is what happens while you’re busy making other plans.”

Is there any one Moonalice poster that is your favorite?

DL: That is so hard because these are like my babies. What is great about doing these for Roger and the band is that I get to explore lots of different graphic styles directions and genres. It is so stretching in different kinds of ways as an artist. Maybe one personal favorite is the one I did for the Lock’n Festival. It’s essentially a gigantic, epic movie crowd scene with these Egyptian dancers coming down this long staircase. It’s really based on an early D.W. Griffin movie. It’s a still frame and there’s a rock and roll band as part of it. I called it The Birth of Rock and Roll.

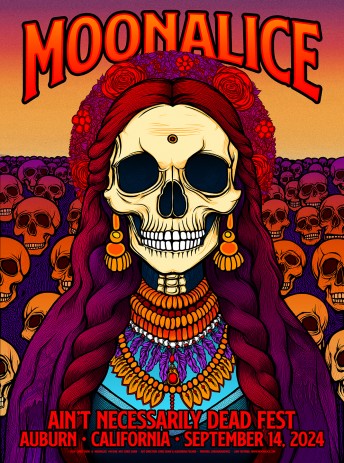

One of the things that I enjoyed doing was being given an opportunity to push the envelope, because I think of myself as that kind of artist. Moonalice has been a great example of that. Right from the beginning, the Warfield, and Radio City posters, I wanted to push the genre in new directions. Adding A female skeleton character and having them as a couple brought more layering onto the Grateful Dead story and presented them to maybe a broader frame of reference.

And so here I am, having a long career as a poster artist, and it was never my intention to become a poster artist at all. I was a starving artist on the banks of the Rio Grande and just like a lot of people in the entertainment and music business, it’s being in the right place at the right time.

The 1970’s was such a dynamic time, with all kinds of invention was going on. Bill was the center of a vast, highly energized universes of creative talent that revolved around him. Bill and I had had an interesting and special relationship because I was the go-to set guy and he was such a theatrically oriented entrepreneur. Bill had this long history of commissioning posters and from his standpoint, it was the creation of it that was the exciting part.

He was very much an existentialist, and he told me that that he loved putting it out there to an artist and then the moment of presentation to him, was like this moment of elation. He had this love and thrill of seeing this brand-new thing for the very first time. He approached our work relationship with me in that same kind of way, that the beyond approving the original drawing, he never wanted to see it until showtime.

I think he and Roger share that.

DL: I think so too. Because with roger, you know, he’s always been very hands-off. The only exception was that he has a little fetish with a dog character called Pokey. That’s why Pokey shows up in a lot of my Moonalice pieces. Most of the time it’s because he’s specifically asked for him. Sometimes I’ll just do it as an inside joke or a little special gift to surprising with.

How did you get started in doing posters or art?

DL: Oh, that’s two very, very different things. You know the short story is that I had a painting career in New Mexico and my wife and I lived in a cabin on the Rio Grande. In early ‘73, we came out to visit her parents, who lived in Berkeley, and ended up staying for a while. I started looking around for a job to make a few bucks and then go back home. I accidentally landed a job working as a helper at the at the San Francisco Opera Scenic Shop.

My wife’s younger brother worked downtown for concert promoter Bill Graham as a roadie. He overheard some of his bosses talking about needing a backdrop painted and they were wondering who they could find to do it. He was just there at the right time, and he had enough chutzpah to say, “I’ll bet my brother-in-law could help you.” They called and said they wanted this backdrop painted, and I said, “Sure, of course. No problem, I can do it.” The beginning of working in music was moonlighting for Bill Graham doing rock and roll stuff. In the early days it was mostly doing blow ups of album cover art for stage backdrops.

Very cool. How did your work progress from there?

DL: I did some work for various bands, including The Dead and others. At the same time, I developed a career as a scenic artist and I moved up through the ranks of the Opera Shop to become one of the main scenic artists. So, I didn’t make it back to New Mexico for quite some time.

I eventually became one of the bosses in the Scenic Shop and I had this booming contracting career for rock and roll on the side. This included being the right guy in the right place at the right time for big stuff like doing stage sets for the Day On The Green shows. I was their go to guy and that was my canvas throughout the ‘70s.

It was a big thing creating these giant backdrops for shows Bill Graham was doing at the Oakland Stadium. As it happens, you do a big show and then the next one needs to be greater and greater every time, including some historic stuff like the 1977 Led Zeppelin Stone Henge show. Several years later, that got parodied in Spinal Tap, which was quite a quite a surprise when I saw it in the theater – seeing myself in miniature and being ridiculed on stage, which I thought was just hilarious.

During that period, I got hooked up with various managers at BGP, but early on, I’d say by ‘78, it became kind of a permanent arrangement with Peter Barsotti, who was a very creative and make-it-happen guy. Peter was a great sort of salesman; I mean he could sell ice cubes to Eskimos. We would collaborate on a concept for a show and then I would go and do the design. I always did drawings to scale because we never had any time and if it got accepted, then it needed to be in the shop the next day getting built.

They always got accepted in part because of Peter and the designs were good. As any artist knows, ideas are a dime a dozen; it’s doing what it takes to manifest them that makes the difference. There are a lot of great ideas that never to get off the drawing board, but Peter was good at developing them. He had a special relationship with Bill, so he would go straight to Bill to get them approved. Then 24 hours later I’d be wherever they set me up and I’d be painting. They would usually set me up at the one of the concert halls, primarily Winterland between shows, which had a big floor. We would lay things out on the floor and do it.

That’s fascinating. So you used the floor of Winterland to paint your backdrops?

DL: Yes, and in my Startling Art book, there is a big section of Day On The Green. In fact, there’s some good documentation of the Led Zeppelin show and one of the pictures shows me painting on the floor and Winterland.

When did you start doing Poster Art?

DL: My collaboration with Peter continued and in 1980 he came to me and said, “You want to do a Grateful Dead poster?” There was only one answer to that question. I had been doing Dead scenery and stuff for a while, including the set pieces, and staging for the big New Year’s Eve blowout shows. I was well versed in the Grateful Dead iconography at that point.

It was at the Warfield, and I think it was the first show BGP did after taking over the management of the venue. I am pretty sure it was the Grateful Dead’s first appearance at the Warfield too, so it was kind of historic in that sense.

We pulled out all the stops. We did our usual kind of conceptual collaboration, and I’m not sure whose idea it was, but the year before we had done a male and female skeleton’s flank the stage on New Year’s Eve. We thought… what if we had them outside flanking the theater? Not only as icons but protective spirits of a sort. We had this concept, and I did some more finished drawings which Peter took to the band, and they loved it. I was off and running.

For that show, I ended up doing everything, not only the poster, which became the hand bill, but I think there was a t-shirt. We did this big marquee where we took those original skeleton figures, which by that time Peter had given them names of Sam and Samantha. They were about 15 feet high, and we hung them on the outside of the building. Then they had me do a banner, which was a recreation of the sign that used to hang on Winterland, which was the quote from Bill Graham about the Dead, which was, “They’re not the best at what they do, they’re the only ones that do what they do.”

And so that that created this whole outside facade decoration. During the shows I was backstage, down in the basement, doing all these set pieces for the stage. They were mostly just big recreations of iconic images – Steal Your Face, Skull And Roses and such. There was maybe half dozen of them, and they pop up all over the place. They used them in subsequent Grateful Dead shows. They just kept using them over and over, but originally, they were done at the Warfield.

The Warfield was such a big success, they asked me to do their next show at Radio City Music Hall. They wanted me to do a matching poster to the Warfield poster. I did the Radio City poster and sent it over them. The Dead being The Dead, they never asked permission to do anything and when they got there, we hit a wall when it turned out that Radio City Music Hall facade is their corporate logo and Trademark.

They slapped a million and a half court injunction against any more sale or distribution of the poster. In a weird ass backwards kind of way, it turned out to be a good thing because it became the most outlawed Grateful Dead posters of all time. And unfortunately, it is also the most bootlegged poster of all time as well.

At that point, did you migrate to doing mostly poster art, or were you still doing both?

DL: No. In fact, at the time in my mind, it was just a thing to do. Just another project and it was the last thing in my mind that it was a career change. It was just an extension of what I was already doing. By 1981, Bill had set me up at Winterland, which by then was a condemned structure and empty building. Basically, as his lead stage designer and primary scenic artist, I was still hands-on and it was still my art form that I had literally invented throughout the ‘70s. I was very reluctant to let that go and they were reluctant to let me go.

That summer I did several shows with my crew of ninja rock and roll scenic artists. That included a big Journey tour, that was based on Mouse’s Escape album cover Then we did the ‘81 Stones Tattoo You tour, and we were all lucky to survive that. The Stone’s thing was a whole story in itself, including a disaster on the road that required a redesign and a whole new, all-weather version. After that was over, I came back to Santa Fe where I did some rock and roll things, like the stage for the US Festival.

So, those crazy days of rock pioneering for Bill are long gone but I still get to occasionally play in the rock & roll sandbox with Roger and Moonalice and it's a wonderful thing!